The Smoltsov report – analysis and comment

Texte from the Report of the Swedish-Russian Working group, Stockholm 2000

“As the Smoltsov report is the only document that has something definite to say about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate, further analysis and comment is necessary. In the first place, a representative of the working group from the Russian Ministry of Security talked to the prison doctor’s son, Viktor Aleksandrevitch Smoltsov (who refused to meet the interview group on the grounds that he had nothing further to add to the details given below). The son was 23 years old in 1947 and already employed in the security service. He stated that his father was unexpectedly called to his work on an evening in July 1947. This was unusual considering that he suffered from heart disease, did not therefore work full-time and was preparing to be discharged. His father did not return until the following morning and then said that a Swede had died in the MGB inner prison (Lubianka). This story must be treated in the same way as every other oral communication; it comprises a version which is not sufficient proof in itself.

“As the Smoltsov report is the only document that has something definite to say about Raoul Wallenberg’s fate, further analysis and comment is necessary. In the first place, a representative of the working group from the Russian Ministry of Security talked to the prison doctor’s son, Viktor Aleksandrevitch Smoltsov (who refused to meet the interview group on the grounds that he had nothing further to add to the details given below). The son was 23 years old in 1947 and already employed in the security service. He stated that his father was unexpectedly called to his work on an evening in July 1947. This was unusual considering that he suffered from heart disease, did not therefore work full-time and was preparing to be discharged. His father did not return until the following morning and then said that a Swede had died in the MGB inner prison (Lubianka). This story must be treated in the same way as every other oral communication; it comprises a version which is not sufficient proof in itself.

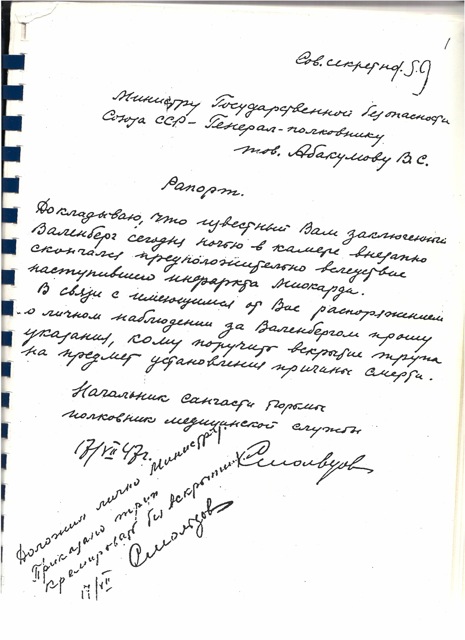

In an effort to determine the authenticity of the Smoltsov report, it was decided at an early stage to have the handwriting analysed by experts and to subject it to a technical investigation. The Russian side undertook to do this at an institute of forensic expertise at the Soviet Ministry of Justice (App. 48). As far as the technical analysis was concerned, their conclusions were that the report could have been written on the date mentioned, i.e., 17 July 1947. It was not possible to determine by means of a chemical analysis (of ink and paper) the exact point in time on which the report was created because there is no method of determining the absolute age of a document based on changes in the material due to its age.

An analysis of the handwriting (App. 49) was made by comparing two other documents said to have been written by Smoltsov. The Russian experts concluded that the same person had written the texts. Differences in the speed of the writing and structure were said to be due to the greater care given to the report, which was written more slowly, than the more careless and the comparative documents which were written at greater speed.

The National Laboratory of Forensic Science undertook the Swedish analysis (App. 50). As far as the style of writing was concerned, they concluded that their observations during the investigation do not give direct reasons to doubt that the report and the comparative material were undoubtedly written by the same person. However, they pointed out that there was no absolute guarantee that the comparative material (a curriculum vitae and a formula from 1940) had really been written by Smoltsov. A new investigation in which a medical certificate was also included confirmed and consolidated the National Laboratory’s earlier observations. Furthermore, it partly strengthened their earlier evaluation of the significance of some of the similarities as an indication of identity. To sum up, it was concluded that the same person had written the Smoltsov report and the comparative documents. The National Laboratory also noted that the Russian method of handwriting analysis differed somewhat from the Western European, and particularly the Anglo-Saxon approach. The greatest difference lay in that the

Russian method allowed a more categorical conclusion to be drawn than the Swedish.

A reservation in the National Laboratory’s final report concerned a newspaper article concerning the discovery of a forgery unit on the premises of the former Central Committee. Ink and paper were found there, inter alia, carefully dated according to their various years of origin. The National Laboratory also assumed that the staff had access to people who were proficient in imitating other people’s handwriting.

The National Laboratory technical analysis (App. 50) was not particularly comprehensive but was principally based on the Soviet investigation. Some samples of writing in ink were taken and saved for future analysis as the present method of age determination was not felt to be sufficiently advanced. Nevertheless, the Soviet observations were deemed to be reasonable. The National Laboratory reached a slightly different conclusion regarding the fibrous composition of the paper, but found the Soviet conclusions fully reasonable and not refuted by their own investigation. Thus, although there is much to indicate that Smoltsov was the author of the report, it cannot be one hundred per cent scientifically proved. In the Swedish view, the possibility of a forgery cannot be entirely discounted.

We must now consider a number of problems relating to the Smoltsov report. First of all, it should be said that the report by no means fulfils the formal requirements for documenting a prisoner’s death in a Soviet prison. Susan E. Mesinai made an exhaustive analysis of the report’s shortcomings on pages 16-17 of her report No Time to Mourn.

The first question at issue is the likelihood of a prison doctor writing a report of this kind direct to the Minister of State Security. According to security officials of the period, the normal procedure would have been for Mironov, the director of Lubianka Prison, to report to Abakumov. Smoltsov was far too subordinate. On the other hand, most of the people whom the group interviewed did not discount that Abakumov may have personally assigned Smoltsov to keep an eye on Raoul Wallenberg, and to report immediately to him if anything happened. What does this kind of assignment tell us about the treatment Raoul Wallenberg received?

It was clearly not a normal situation. If Raoul Wallenberg was in good health and well-treated, as several of his fellow prisoners stressed (at least in 1945 and 1946 and in March 1947 as well, according to Kondrashov), there would be no need for a special arrangement of this kind. According to a heart specialist who was consulted, there is a million to one chance that a healthy 35 year-old without any history of heart disease would suddenly die of a heart attack (or cardiac infarction as the report described it). A sure diagnosis of cardiac infarction can only be made on the basis of an autopsy carried out within 24 hours after death has occurred (see pages 22-23 of the above-mentioned report by Susan E. Mesinai). Even in the event of such a death taking place, the prison doctor would not need to ask for instructions, but could decide for himself whether to carry out the normal procedure of a post-mortem examination.

One theory is that Smoltsov immediately suspected that Raoul Wallenberg’s death, if he died then, was not due to natural causes and therefore asked Abakumov for instructions on how to deal with the body. This presupposes that Raoul Wallenberg was either poisoned or received such harsh treatment for a while that he died. In this case, the wording of the report may in some way be genuine, i.e., written by Smoltsov and reflecting his superficial observations even though he suspected that there was more to it than met the eye. On the other hand, had Raoul Wallenberg been shot by a firing squad, the report would have been composed differently. Smoltsov would probably have been ordered to write the report as a cover up, for use as required, i.e., to have ready in case the official version, published later, did not hold up. Cardiac infarction was otherwise one of the causes of death frequently used to conceal unnatural death, i.e., death by execution or ill-treatment. Finally, the report may have been fabricated at a later date. Perhaps the misspelling of Wallenberg’s name argues against this theory, although the idea of a deliberate spelling mistake cannot be ruled out as a means of adding credibility to the document. If this were so, the report could of course conceal anything and everything, including Raoul Wallenberg being kept in isolation somewhere.

To return briefly to the Gromyko memorandum of 1957. As emphasised above, the Soviet side treated the Smoltsov report with noticeable caution in the memorandum. Were they genuinely uncertain about the value of the report as evidence, or were they afraid that the Swedes had more information up their sleeve with which to refute this version? Is it reasonable to assert that the report may have been fabricated in 1956 (Smoltsov died in 1953)? Would they not have arranged to put forward much more convincing evidence of Raoul Wallenberg’s death, drafted according to all the formal rules. It would have created a greater opportunity for putting an end to the whole case. However, there was still a risk that Sweden could refute it with evidence which they had not yet submitted – for example, from one of Raoul Wallenberg’s fellow prisoners – which could disprove even this evidence. It was therefore better to present a slightly vaguer version from which retreat was possible. It has been satisfactorily proved that the reply they desired to give to Sweden in February 1957 was not the whole truth but, at best, ‘a half truth that would do’. Their uncertainty regarding the tenability of the reply is particularly evident in their efforts to hold advance discussions with Swedish representatives about drafting a reply.

Little credence can be given to the interpretation that those drafting the memorandum were unaware of whether Smoltsov’s note was genuine or dictated by Abakumov, and that they wanted a line of retreat if it was later proved that Raoul Wallenberg was executed or hidden away. To someone like Molotov, who certainly had a hand in the dark deeds of 1945-47, it may have appeared simpler, though risky, to confess to Raoul Wallenberg’s execution, if this were true.

In an internal memorandum dated 8 February 1957, Arne S. Lundberg, then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, wrote that it was unlikely that Smoltsov, who was personally responsible for Raoul Wallenberg, did not receive orders to destroy this evidence as well (i.e., the Smoltsov report) if it were true that other evidence had also been destroyed. The reply could have been drafted as it was even if Raoul Wallenberg had been lost, or was in very poor condition. The death certificate was issued to put an end to the matter. As Lundberg pointed out, it was strange that there was no reference to any witness, nor was one ever found. The Smoltsov report could be said to contain eveything the Russians desired; it explained how, when and where Raoul Wallenberg died, and laid the blame on Abakumov. The result was both ideal and educational. It might be suspected that the document was falsified, and the reason for this was partly educational and partly the need to explain the long delay. Lundberg also felt that the Russians could easily have provided an absolutely definitive statement, had they so wished. If they had lost Raoul Wallenberg, or he was in poor condition, they may well have reasoned as follows: Should the Swedes turned up evidence of Raoul Wallenberg being alive after July 1947, we can always get away with it by referring to the vagueness of the reply.

Even if the Smoltsov report was not forged in 1956/57, it is in any case unclear exactly where, how and when it was found. The Gromyko memorandum mentions the prison medical service’s records at Lubianka Prison. No such records exist, or have existed, according to the FSB deputy head of archives and member of the working group. On the other hand, special journals existed for recording details of prisoners visits to the doctor. The prison medical service material was included as part of the prison records, and most of the material relating to prisoners was kept in their personal files. The former Foreign Ministry official mentioned below once said that at the time of the 1956 inquiry, he suggested taking a look at the medical service records where the report was later found in material left behind by Smoltsov, the prison medical officer. Nevertheless, it is not exactly clear where and how it was found. A KGB official assigned to search prison records in 1956 for evidence that Raoul Wallenberg suffered from some illness, has said that he did not find any Smoltsov report. “It must have turned up there later on”, he said.

The head of the Foreign Ministry archive thought that theoretically the Smoltsov report could have come from the so-called ‘extraordinary events’ file which has a limited archive life. The report could have been removed from this file and saved since the time of the inquiry. Lubianka Prison’s ‘extraordinary events ‘ file for 1947 has in fact survived. It was examined without finding anything remarkable for the month of July, with the exception of a female prisoner who attempted to commit suicide.

The FSB also state that since 1956 the Smoltsov report was kept as an individual paper in a file or folder containing correspondence on the Raoul Wallenberg case.

In an official document delivered to the working group in 1992 (App. 52), Zhubchenko, head of the central archive of the Russian Ministry of Security, assured us that:

1) The Lubianka and Lefortovo prison nomenclature files for 1945-53 (in which reports, notices and certificates concerning extraordinary events – including deaths – were entered) contained no note indicating that the Smoltsov report had been removed (from Lubianka and Lefortovo);

2) Other Lubianka files for 1947 in which the Smoltsov report might have been placed, were destroyed according to a document dated 12 August 1955, viz.,

- correspondence about prisoners with departments and prisons,

- copies of accompanying letters to memoranda and files on prisoners’ health status’, top secret correspondence about prisoners with the investigative and sentencing authorities,

- general correspondence.